Scepticism for beginners

This blog post was written by Mark Wearden, an experienced NED, a nationally recognised authority on corporate governance, a prolific author, and an outstanding trainer and mentor.

The Greek origin of scepticism is the word ‘skepsis’ which translates as examination, inquiry into, and hesitation or doubt. The philosophical development of this idea leads to three concepts

- Doubt stimulates informed challenge and inquiry

- All judgement about truth must be suspended – we need to keep an open mind

- Our ideas are not finite, otherwise no final judgement can be made – as human beings we are regularly forced to make decisions despite out continuing propensity to doubt.

Judgement requires the use of the sceptical human brain to challenge and enquire, but then to still make a decision.

There has been, and continues to be, much research and consideration of the way in which the human brain works. Not least today, in an attempt to reproduce such functionality through robotic artificial intelligence. This has often been represented as the difference between left and right brain thinking.

- Left brain thinking being the normal day-to-day logical, sub-conscious reactions which allow us to function in our day-to-day lives as human beings

- If we are someone who tends to just accept things as they are, then we could be described as having a dominant left-brain attitude

- Right brain thinking being the lateral, creative abilities which lie within each of us

- If we are the type of person who is always challenging, then we could be described as having a dominant right-brain attitude.

Of course, in neither case, does that exclude us from regularly using both perceived sides of the brain. That is required to be a human being, otherwise we would never be able to deal with the unexpected – eg the sudden red light as we are driving along minding our own business.

The way in which we are perceived by others as using our brains will influence our behaviour, and therefore we move into a constant iteration – we behave in a certain way, that is perceived in a certain way, we react and therefore behave in a slightly different way etc etc.

For the purpose of these notes and thoughts, this left/right modelling could be used to suggest that scepticism requires the ‘right-brain’ to challenge the ‘left-brain’.

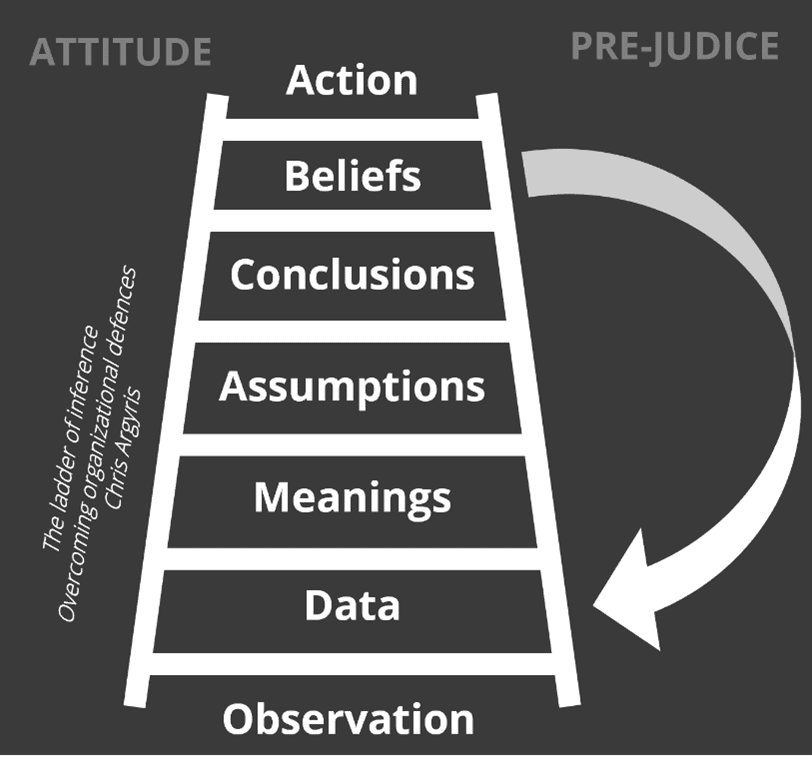

We need to take this thinking one step further and for this I am using a concept called the ‘ladder of inference’ originated by Chris Argyris[1].

Argyris used his ‘ladder’ to consider how the brain enables us to take any action, from the most simple to the most complex. His explanation was that the brain moves through a series of stages (steps) based around the initial observation (through all of our senses), with the assimilation of data and then the iterative sorting and selection which enable us to take a specific action.

A key learning from the use of the ‘ladder of inference’ model is that the penultimate stage before we take action – known as the belief stage – combined with the result of the action itself, will then inform the earlier stage of ‘data filtration’, which allows us to retain what we perceive as relevant for our ongoing approach to life (our attitude).

This process can be described as the basis of prejudice or bias within the brain.

[1] Chris Argyris, Overcoming Organisational Defences 1990

Prejudice, because if we take the word to its root ‘pre-judice’, we can see that our brain requires us to pre-judge many situations on a constant basis. The word prejudice tends to be used with negative connotations, but we require this action of prejudice for every aspect of our behaviour as a human being.

Cognitive bias

This prejudice is the basis of what has become known as natural or cognitive bias, and there is only time here for a brief introduction.

Different publications identify differing numbers of biases, with the extreme perhaps being the ‘cognitive bias codex’ (available on the web-ride and the screen) which identifies 180+ different biases!

The following ten common biases are recognised as a natural part of the way in which we behave as human beings We must be prepared to search within ourselves to learn and understand how and why we might be behaving and reacting in certain ways, and therefore we become better able to understand how and why others behave or react in certain ways.

| Hindsight | being wise after the event |

| Outcome | focus on vision rather than reality |

| Confirmation | selecting what agrees with our existing beliefs |

| Anchoring | using a benchmark to judge |

| Availability | not looking beyond the obvious |

| Groupthink | fitting in with the crowd – ‘when in Rome…’ |

| Overconfidence | we know better than others |

| Recency | not looking far enough back |

| Stereotyping | box thinking |

| Blind-spot | lack of 3600 vision |

In our consideration of scepticism, we need to be aware of our own cognitive biases, and then also accept and recognise that the biases of others will often be different to ours.

Scepticism requires us to recognise and move beyond the biases, but of course, as recognised by the Greek philosophers, at some we point we do still have to decide – no-one will thank a director or manager for failing to meet deadlines because they are trying to reconcile the figures in front of them with the ‘true and fair’ nature of their biases!

The Boardroom Effectiveness Company offers a wide range of training, coaching and consultancy services aimed at helping boards be more effective. Take a look at our full range of services or give us a call on 01582 463465 – we’re always happy to help.