Risk and reputation

Before reading these thoughts, it will be useful if you have already considered my earlier article on risk appetite and risk tolerance.

Risk

On a regular basis we need to reconsider the significance of what is meant by RISK and why our risk behaviour has such an impact on the reputation of ourselves and those around us.

Risk conjures up an immediate and powerful meaning to the human brain. The taking of risk can appear to move a person from their previously predetermined path and lead them to behave in a manner that had previously seemed unlikely. The natural reaction is to think big and dangerous, but even opening a door is a risk – are you ever 100% certain what is on the other side?

In an organisation risk often tends to be viewed as a longer-term consideration, or a recognition of what has already happened, but risk is now and immediate. The impact (positive or negative) of taking a risk is felt at the moment when that risk does or does not materialise – that is now – everything else is future speculation.

Take a simplistic personal perspective.

- I devise a STRATEGY to make myself a cup of coffee.

- I step back (unusually) and consider the RISKS involved (burns, electric shock, breaking a cup etc etc)

- I CONTROL those risks through taking perceived sensible precautions.

- That, of course, does not stop a risk occurring if I have miscalculated in some way, or I drop the cup or the kettle etc

- The lessons that I learn from this iteration will inform my next strategic decision to make a cup of coffee and increasingly I ignore the ‘stepping back and considering’ phase and just base my action on presumption.

Every decision that we make about what we are or are not going to do has these three same essential dimensions, this applies to us as individuals and it applies to the collective decision-making processes within any organisation.

This is epitomised in the model.

The triangulation requires us to step back from our internet world of immediacy and take time to reflect, consider, debate and challenge our strategic objectives.

From a corporate perspective this could be seen to be at the heart of what is required from directors under the 2006 Companies Act s172 with its stakeholder considerations and commentary. The requirement is wider than just ourselves and our immediate surroundings, we have that wider accountability to our stakeholders, and any large company now has to report on how its directors have considered the stakeholder impact (what is the strategy and how does it impact the stakeholders; what are the perceived risks to the stakeholders; how are we trying to control them)?

It is important that we identify, evaluate and address the dangers and their ultimate wider impact to ourselves, our firm, our clients, our profession, our stakeholders – our reputation.

- Identify

- What is the risk?

- Why is it a risk?

- Evaluate

- When might a risk impact me or others?

- How do I assess the potential damage?

- Address

- Who can make a difference?

- Where do we need to take action?

Our reputation, as individuals and as organisations is based upon how others perceive our approach to risk (even though others may not recognise that is really what they are assessing).

It is key to therefore consider and understand our own perspective – am I risk-averse, or am I a risk-seeker? In a workshop situation most people will answer “well that depends” or “somewhere in the middle”, but I would maintain that all of us are more inclined in one direction or the other at different phases of our lifecycle, and it is important to recognise where we are.

- A risk-averse person (or group (of people)) looks for certainty of outcome and is therefore prepared to sacrifice opportunities that might exist for change.

- Risk aversion can often lead to an intolerance of challenge and therefore an overreaction to any threat to the status quo.

- Facts are often preferred to theories.

- A risk-seeking person (or group (of people)) accepts that life is full of options and uncertainty and such a person has confidence in using their abilities to counter whatever they may face. Threats that are seen by the risk-averse person are very often not even considered as threats by the risk-seeking person

- Risk seeking can often lead to a dangerous dismissal of the realities that confront a person or organisation

- Imagination is often preferred to facts.

This is a demonstrable example of what is known as our cognitive bias, the basis of our behaviour based upon the accumulation of all of our learning experiences (and hence beliefs) at any particular point in our life. You can read aligned commentary on this in my article on scepticism.

What are your biases? How and why do you make the decisions that you do? Why do you not see the risk, when someone else does – and vice versa?

Reputation

Reputation can be defined as

“the beliefs or opinions that are generally held about someone or something”.

This has to be set in the context of the forces of societal expectation (the societal biases) under which we are all required to operate and the views of the other people who surround us and our organisation (the stakeholder biases). The reputation of an organisation or a person is only ever based around the opinions held and developed by one or more other people.

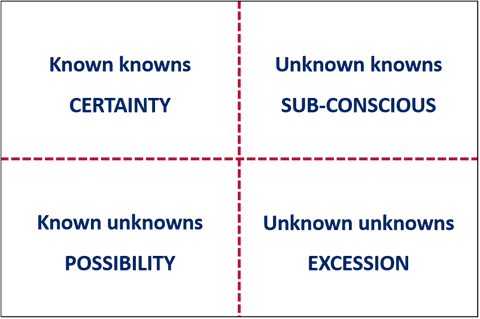

Whatever situation requires our judgement or opinion, there are only four potential scenarios:

- If we have full knowledge of all required facts for our decisions than we are faced with CERTAINTY.

- If we have doubts about some aspects of the evidence we are faced with then we are faced with POSSIBILITIES.

- If we feel that, based upon our experience, something is not quite right then we are relying on our SUB-CONSCIOUS.

- If we are faced with a situation we do not understand and had not previously contemplated then we are faced with EXCESSION [1].

I like to place these concepts in a matrix to challenge us to really consider what it is that we are dealing with. The matrix uses the concept in alignment with the relationship between the known and the unknown. In February 2002, Donald Rumsfeld, US Defence Secretary [2] was asked about the likelihood that the Iraqi government were supplying terrorist groups with weapons of mass destruction. His comment was

- There are known knowns; things we know that we know.

- There are known unknowns; things that we now know we don’t know.

- But there are also unknown unknowns; things we do not know we don’t know.

The concept of the unknown unknown is sometimes referred to as a black swan event, any situation where we are faced with something that takes us by surprise, something which in our conscious mind we had not previously considered likely to occur. This concept of the Black Swan is epitomised and discussed at length in the writing of Nassim Nicholas Taleb [3];

- The Black Swan exists but is highly unusual and therefore lies beyond our expectations, and outside our conscious awareness.

- The appearance of a Black Swan will cause an impact upon a situation and will affect the conscious awareness of people involved.

- The Black Swan event will be explained in a manner that suggests that we already knew of its likelihood (Taleb’s phrase here is retrospective predictability).

Conclusion

How do we best protect our reputation?

- WE must always take the time to recognise the risks that we are about to take.

- WE must always consider how a diversity of stakeholders may react to our behaviour and opinions.

- WE are in control of our reputation through the actions that we take and the decisions that we make, every day of our lives.

The Boardroom Effectiveness Company offers a wide range of training, coaching and consultancy services aimed at helping boards be more effective. Take a look at our full range of services or give us a call on 01582 463465 – we’re always happy to help.

[1] The word “excession” is borrowed from the novel of that title by the late Iain M Banks, where it is used to describe any problem sitting outside current contextual awareness.

[2] Rumsfeld, D., Known and Unknown: A Memoir (2011)

[3] Taleb, Nassim N., The Black Swan. (2010)

This post was written by Mark Wearden, an experienced NED, a nationally recognised authority on corporate governance, a prolific author, and an outstanding trainer and mentor.